The Australian: Into their arms: a safe place to call home

Author: Christine Middap

Published: June 18, 2023

Source: The Australian

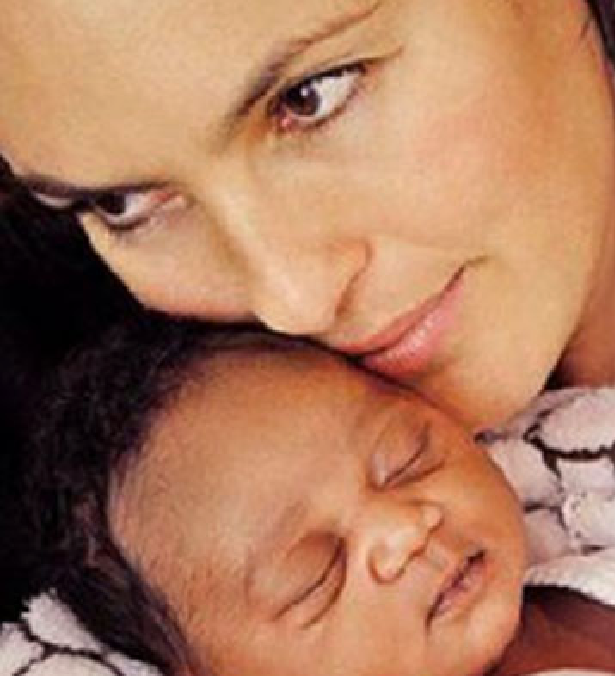

Moe, Caleb and Memphis Lainson are part of a dwindling number of children adopted in Australia: Moe was one of 208 adoptions in 2021-22, a record low.

Little Moe Lainson walks around his large family home with a certain confidence that there will always be a set of arms to fall into, for there are benefits to being the baby of the group.

He scrambles into his mother Sarah’s lap and buries his head into dad Simon’s neck. He leans into his big sister Amelia and older brother Ben, wedges himself between Caleb and Memphis. “These are my brothers,” Moe declares as he links his arms with theirs.

He’s only just turned five and Moe is keenly aware of this big family and how he came to be in it. He’s adopted. So are his siblings Caleb, 9, and Memphis, 8, and they tell me this as if it’s the most normal thing in the world. No secrets, no whispering of a word that – due to past practices well beyond their lives – is still freighted with loss and suffering for older generations.

The three boys are part of a dwindling number of children adopted in Australia: Moe was one of 208 adoptions in 2021-22, a record low according to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). The previous year, Memphis and Caleb were two of the nation’s 264 adoptions.

They were removed from their family home due to neglect and violence, and placed into short-term foster care when they were just babies; the two older boys spent more than a year in the system and had multiple placements.

When a court determined there was no possibility of returning to their parents, they were matched with the Lainsons, a Wollongong couple with three biological children who had waited years in the adoption pool.

The three boys are part of a dwindling number of children adopted in Australia: Moe was one of 208 adoptions in 2021-22, a record low according to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). The previous year, Memphis and Caleb were two of the nation’s 264 adoptions.

They were removed from their family home due to neglect and violence, and placed into short-term foster care when they were just babies; the two older boys spent more than a year in the system and had multiple placements.

When a court determined there was no possibility of returning to their parents, they were matched with the Lainsons, a Wollongong couple with three biological children who had waited years in the adoption pool.

Renee Carter, chief executive of advocacy group Adopt Change, says it is surprising that adoption numbers are so low, given the need is so high: more than 46,000 children are living in the child protection system away from their families, 68 per cent for two years or more.

With a shortage of foster carers, she said about 4000 children, some under the age of four, were living in “institutional care” in group residential homes or with rostered carers in motels.

“We’re not talking about trying to adopt out children who have an opportunity to go home. But we have children desperately in need of a permanent, stable, nurturing family home and, in some instances, the best option for them is adoption,” she says.

Carter says the Covid pandemic and use of alternative permanent care or guardianship orders had contributed to the low number of adoptions. But she says a level of fear and stigma still surrounds the practice, even though things have changed since the dark days of children being taken from single and unwed mothers or forcibly removed from Aboriginal parents, giving rise to the Stolen Generations.

“Now we are talking about open adoption where there is still a relationship and contact with the family of origin so it’s more a concept of belonging in two families where one has legal parental responsibility,” she says.

Read the full story here.