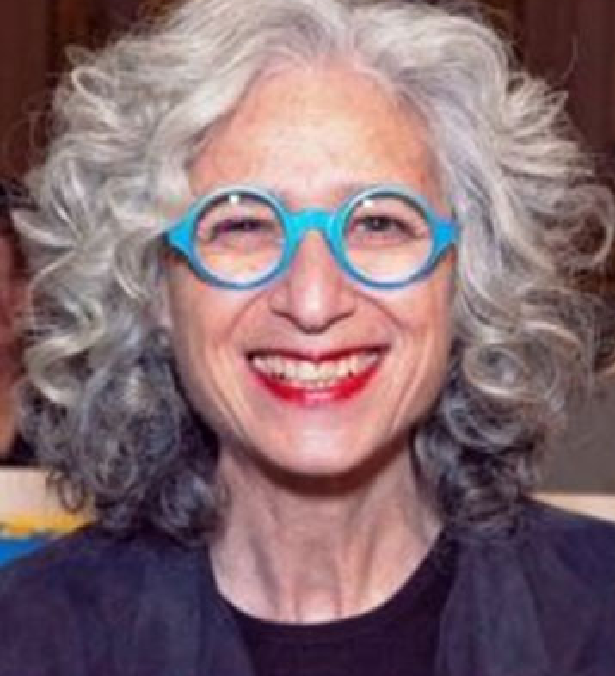

My Story, My Connections: Emma

Emma’s story – two child protection systems worlds apart

When Emma told her new work team that she had two adopted daughters, they looked at her as if she’d just confessed to being a terrorist.

“Adoption is such a taboo here,” she says, “it’s only ever mentioned in a negative context”.

Emma was a child protection team leader in the UK. She took up a similar role soon after emigrating to Australia in 2014.

Emma’s time in the UK showed her that adoption can be done openly, ethically and effectively. Over time, she has been able to share her experience of this with her new Australian colleagues. However, she still has significant reservations about their decision-making ability in a system that is geared towards always keeping birth families together.

Working in child protection in the UK, Emma had seen many kids grow up in toxic family environments who were in need of an alternative, safe home. For this reason, Emma and her partner Sam expressed an interest in adopting children in government care in May 2012, then chose a local adoption authority who placed them on a three-day training course.

This was followed by a rigorous six-month assessment process. “It was so intense,” says Emma, “they really test your strength as a couple and your ability to look after traumatised kids”.

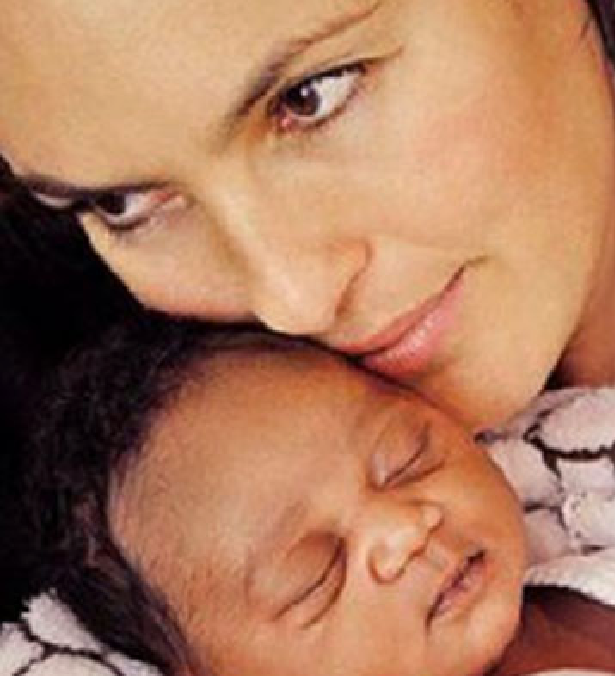

The couple were approved to adopt in November 2012, and within three months were taking care of two-year old Rebecca and her five-month old sister Megan.

“Couples must wait at least 10 weeks before applying for an adoption order. This allows parents, kids and social workers enough time to determine whether the match is right,” says Emma.

By August 2013, Emma and Sam celebrated a finalised adoption order and the start of a new family.

“Our first year as parents was the hardest of our lives,” says Emma. Rebecca in particular experienced real attachment issues due to the early trauma of her frequent moves and abuse by her birth parents. She had lived in five different homes before her first birthday, and was a victim of family domestic violence.

Emma says: “People think babies don’t remember violence but they do. Rebecca went through a healthy cycle of loss which became hardest in the anger stage; when she’d spit, scream and kick. We really had to show patience and empathy. We followed a therapeutic parenting approach called PACE developed by Dan Hughes.”

Emma and Sam were also assisted by specialists helped them discover that drawing was the best therapy for their daughter – sketching out her trauma history would calm her down. In the UK, the family had access to the nationwide Adoption Family Support Service – an 11,000-member government-funded charity group that provides training, a helpline and online community forum for adoptees and their adoptive parents. In Australia, by contrast, post-adoption support is scarce.

Nevertheless, Emma and Sam continue to regularly teach their girls about their history. The children have their ongoing life storybooks, memory boxes and relevant information about why they were adopted. There are letters exchanged annually between the family and the birth parents.

“Adoption is open in the UK. Birth parents are even invited to court to contest an adoption order. But the onus is on them to demonstrate they’ve changed and that the children won’t be harmed again if returned home. The process is very child-focused,” she says.

Emma believes this contrasts markedly with the “adult-centred” child protection systems she has experienced since coming to Australia.

“Here, birth parents are invited to court but often don’t turn up. Judges adjourn, adjourn and adjourn again. Parents are given so many chances, while children are shuffled from one temporary carer to another. Courts don’t consider adoption. It’s family preservation at all costs,” she says.

Emma says that caseworkers in Australia have a really tough job, having to constantly make difficult decisions in stressful environments with limited resources. “There are caseworkers that really want to make a difference in children’s lives, but they’re being held back by a broken system,” she says.

Further, she adds that their education is often misdirected and inadequate – there is a lack of understanding of evidence-based practice, poor assessment skills and under appreciation of how domestic violence affects kids.

“Abuse depends on how hard someone is hit. It’s only serious if bones are broken” is a comment she once heard at a training seminar.

Emma has seen cases of abused children being abused again soon after being placed with kinship carers and also after being returned to birth parents.

But Emma is hopeful for change. “Early intervention and foster care will only help so many families. There will always be those for whom such policies won’t work. As more and more children enter care, governments will have to start listening.”

Please note: identities have been changed to protect confidentiality.

Emma’s view as a child protection practitioner on the two different systems she has experienced

| United Kingdom | Australia | |

| Planning timeframes | Strong emphasis on timely decision-making and processing. Local authorities have six months to assess and approve adoptive parents and six months to make decisions on whether a removed child of any age can be returned to their birth parents. Local authorities are well-resourced to provide training and support for carers, adoptive parents and children. | Permanency planning is policy but not legislated in many jurisdictions, meaning children are susceptible to drift and delay. In states where permanency planning is legislated, timeframes vary, ranging from 6 to 12 months in NSW (depending on a child’s age) to 12 to 24 months in Victoria. |

| Court processes | Child-centred. Decisions need to be made quickly to minimise disruption in children’s lives. Birth parents are given the opportunity to contest adoptions, but onus is on them to prove changed behaviour and circumstances. Judges reluctant to move children once they develop an attachment to carers. | Adult-centred. Birth parents given limitless opportunities to address their problems. Court hearings adjourned over and over again if birth parents don’t show up. Children known to transition between numerous homes before decisions are made. |

| Role of adoption | Adoption is seen as an option for children who have been harmed when reunification to parents is not possible, kinship care not beneficial or where children are not able to have their needs met with stable long-term foster care arrangement. Adoptions are open, children are educated about their history and contact is maintained with birth parents where possible. | Adoption is very rarely pursued as an option for children in care. Emma recalls a permanency planning training session when adoption was only once mentioned, in the negative context of forced adoption. In this session, guardianship orders were discussed in a rushed manner which suggested there were too many barriers to achieving this for a child in foster care. |

| Potential adoptive parents | There are two routes to adoption – to be assessed as an adoptive parent without needing to be a foster carer or to be assessed as a foster carer with potential to adopt in the future, known as concurrent planning.Regular information seminars and training sessions available on how to become an adoptive parent and being assessed to do so. Local authorities encourage adoption and are quick to provide information. They also provide post-adoption support throughout the life of the adopted child.A diverse range of people adopt children of all ages in the UK. Emma has worked with adopters who were older and whose children were teenagers before they adopted. She worked with families who had biological children and wanted to adopt children who were older and harder to adopt due to disability or emotional issues. | Difficult to find out about adoption. Often long waits for information sessions. Little support or encouragement from child protection agencies. Very slow approval processes, it can take between four and seven years to adopt. In most jurisdictions, the only route to adopting children in care is to first become a foster care.Emma is aware of Australians who want to adopt who have sought guidance and advice from UK adoption agencies in the hope they can adopt there. |

| Basic philosophy underpinning child protection system | Emphasis on making timely decisions in the interest of the child. Authorities quick to intervene when there are reports of abuse. Open adoption is one of various options for children and is only taken once all other permanency options have been assessed as not being in the best interests of the child. | Strong emphasis on family preservation. Children only removed after multiple reports of abuse or neglect, with foster care seen as a last resort by many caseworkers. If removed, children are placed within extended families as the preferred option. |