For the care of children: a legacy of complexity

Original source: Law Society Journal

Author: RUBY KRANER-TUCCI

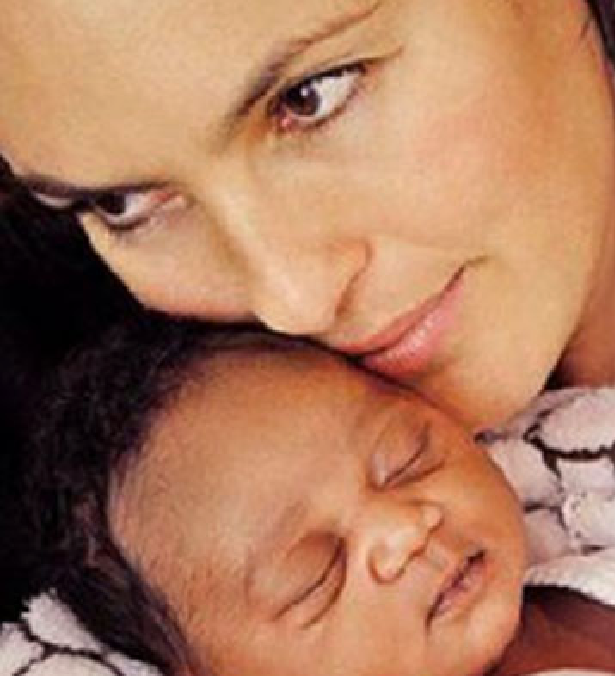

All children should have their future secured through the right to safety, family, and permanency. Current adoption legislation and practice, though haunted by a legacy of delay, confusion and complexity, is highlighting the importance of safeguarding those rights.

Adoption legislation and its associated regulations reflect a complex and fraught legacy for lawyers, prospective adoptive parents and vulnerable young people alike. From the era of forced adoptions; to the adoption crisis stemming from improved access to contraception and abortion; to the explosion of overseas adoptions; and, most recently, to the push for family restoration, the prevalence of adoption has become inextricably linked to the politics of the day.

As a result, the governance and practice of adoption vary across each state and territory. Currently in NSW, adoption can be separated into five types:

- Local adoption, of a child born or permanently living in NSW and including known-child adoptions by a relative, stepparent or carer

- Intercountry adoption, of a child from overseas by a NSW resident

- Out-of-home care (OOHC) adoption, also known as carer adoption, of a child living in foster care by their authorised carer

- Special needs adoption, of a child with disability or special needs

- Intrafamily adoption, of a stepchild or child within the family.

A legacy of length

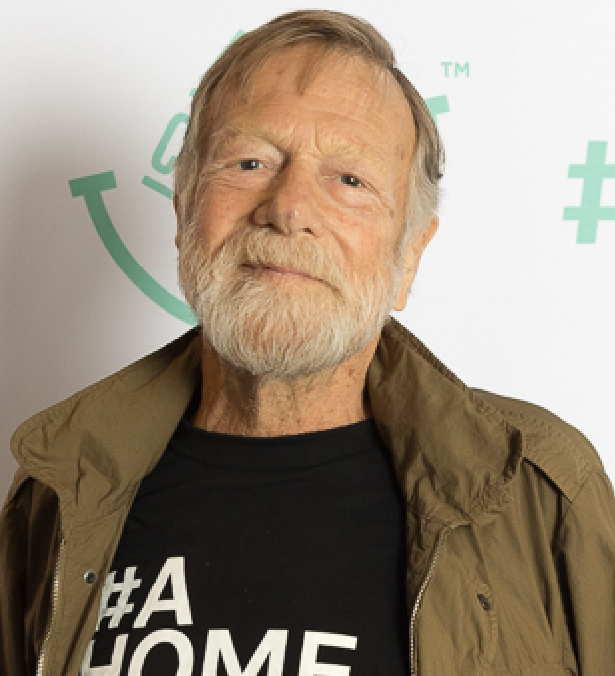

Navigating the adoption process presents a raft of challenges for hopeful parents across the state. Barrister and solicitor Stephen Bourne – a children’s and family law specialist who has spent the majority of his 25-year career practising in NSW – says the Adoption Act 2000 (NSW)(Adoption Act) is “characterised by having lots of hurdles that prospective adoptive parents need to clear”.

“The legal process effectively requires that certain steps be completed before any application is made,” says Bourne, a member of the Law Society of NSW’s Children’s Legal Issues Committee. Bourne currently manages the Family Law Division at the Legal Services Commission of South Australia.

He explains: “The assessment phase is lengthy, which is partly to allow for all relevant information to be received by the [NSW] Department and carefully evaluated, but also to ensure there is an extended period during which the child’s placement with their carers can be monitored more intensively with adoption in mind.”

When it comes to local adoption, for example, the NSW Department of Communities and Justice (DCJ) outlines a process involving multiple steps.

After initially expressing their interest with the state authority, prospective adoptive parents must attend a mandatory three-day adoption preparation seminar. They can then formally apply to adopt, and this application is screened for a subsequent in-depth assessment – reflecting the legislative requirements of the Adoption Act – which typically takes a minimum of three to four months to complete.

If approved, the adoption process will proceed in relation to the proposed child, or the adoptive parents will be matched with a suitable child, a process that differs depending on the child’s specific needs. The DCJ states that it “generally proceeds to finalise the adoption about six to nine months after the child’s placement”.

The adoption is then formalised through an application to the NSW Supreme Court, where the proposed order is reviewed. The final step involves the order being made, including authorisation of an amended birth certificate from the NSW Registry of Births, Deaths & Marriages recognising the child’s adoptive status.

The median wait time for intercountry adoptions, by comparison, is four years – from the approval of the application to the placement of the child – according to the latest data from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). South Korea has the shortest median wait time, at two years, while the Philippines has the longest, at seven years.

In cases where children are adopted from statutory care, a permanency plan incorporating adoption as a future step may be approved by the Children’s Court of NSW under the Children and Young Persons (Care and Protection) Act 1998 (the Care Act). However, Bourne is quick to note that these cases still entail “a full assessment of each carer’s parenting capacity and the child’s needs”, regardless of how long the child has been in their care.

“Adoption-from-care has given many children and young persons the much greater security of a permanent home,” he adds, “compared to the earlier situation where more children and young people remained under the parental responsibility of the Minister and were often subject to multiple placement changes.”

A decade of waiting

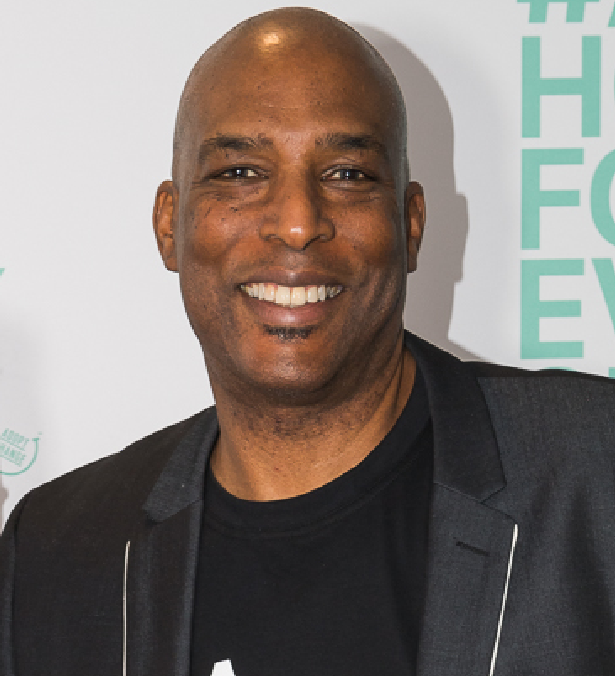

This experience of “hurdles” in the adoption process is reflected in national research conducted by Adopt Change, an NSW-based not-for-profit organisation that supports and educates families and communities caring for displaced children. This research depicts an adoption system plagued by confusion and delays.

A significant majority (almost 83 per cent) of respondents to the 2017 Barriers to Adoption in Australia report said they experienced barriers in the adoption process, particularly in relation to administrative requirements. More than 80 per cent found the adoption process and information surrounding the topic “complex and overwhelming”, while more than half (56 per cent) encountered “unexplained process delays”.

“While there is a strong consensus that any adoption assessment procedures should, quite rightfully, hold families to the very highest standards, these processes can place significant stress on both children and their families,” the report states.

“Some families report undergoing years of assessment and re-assessment. For other families, the adoption process is characterised by stasis, as processes appear to stall for reasons that may not be in any way clear to the families involved.”

For almost 60 per cent of respondents, the adoption process had taken between one and four years to complete; around one third said it had taken between five to nine years; and, concerningly, just over six per cent reported a wait time of ten years or more – demonstrating that permanency is not being fully realised for some children for more than a decade.

Adopt Change CEO Renée Carter says adoptive families “often encounter inexplicable delays and red tape” throughout the entirety of the adoption process. “Whilst we definitely need strict guidelines and processes to ensure children will be safe and supported, the process needs to occur in a timely fashion and without unnecessary bureaucracy,” she says.

Carter adds, “Permanency and meaningful adult attachment are necessary for a child to experience a normal developmental trajectory. Languishing in the care system leaves children vulnerable to placement moves, constantly new case workers, and people who don’t know them making decisions that impact their life … In essence, the government should not be a ‘parent’.”

As well as the considerable length of time involved, adoption in NSW can be an expensive procedure. While there are no fees for foster carers who adopt a child in their care, other programs come at a high price.

The NSW Government estimates the cost for a local adoption in the state to exceed $3,000, which accounts for both departmental and legal fees. Intercountry adoption, by comparison, has a far higher cost, approximately $10,000 – a figure that excludes additional costs such as overseas travel and accommodation, immigration sponsorship, translation fees and other legal expenses. In recognition of the disadvantage these costs may cause, the DCJ does offer fee relief through a Hardship Policy, to assist lower income households looking to adopt overseas.

Reprioritising permanency

The tedious, costly, and complex nature of the current system is a contributor to Australia’s low rates of adoption. Just 208 adoptions were finalised across the country in 2021–22 – down from 264 adoptions the year prior – according to the AIHW’s latest Adoptions Australia report.

Most adoptions – 92 per cent – related to children already living within Australia, with a total of 94 made by carers and 60 by stepparents. Just 16 children were adopted from overseas – a 62 per cent drop from the previous year – reflecting both a global trend of supporting children to remain in their home country, and the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on border closures.

“It’s worth noting that the low adoption numbers do not match the urgent need for thousands of Australian children living in state care who currently don’t have a safe place to call home,” Carter adds.

“The AIHW data [for 2021] from the Child Protection Australia report shows that a staggering 15,895 children and young people are living in out-of-home care across NSW. Nationally, this figure is over 46,000.

“Childhood is fleeting, and there needs to be a timelier focus on either reunification with family and appropriate supports provided to facilitate this, or other permanency options investigated within dedicated timeframes. This is not just reflective of NSW – each state and territory should prioritise permanency outcomes for vulnerable children and young people.”

Interestingly, NSW showed the highest rate of adoption when compared to other states and territories: 131 adoptions, or more than half of all Australian adoptions.

One significant legislative change affecting this prevalence was made in the 2014 Child Protection Legislation Amendment Act, where a new Section 10A was inserted prioritising adoption ahead of having the child remain in statutory care – with the exception of cases concerning an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander child. This approach is reflected in the incorporation of the Permanent Placement Principles in Section 10A, which outlines the following priority order for long-term placements for children:

- A child who has been removed or assumed into care should first be restored to their birth parent(s), in order to “preserve the family relationship”.

- If it is not practicable or in the best interests of the child to return home, the next preference is guardianship with “a relative, kin or other suitable person”.

- If guardianship is not approved, under section 79 an alternative is the allocation of parental responsibility to an agreed upon suitable person or persons.

- Adoption is considered the fourth preferred option, except in the case of an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander child.

- The next option is the allocation of parental responsibility to the Minister.

- Finally, the adoption of an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander child may be considered.

According to Bourne, the general premise of the Permanent Placement Principles focuses on family restoration, which is “likely to provide stability and connectedness” for vulnerable children.

If a child cannot return to their birth parents or to a kinship placement, Bourne says, “then it is well established that adoption – especially adoption where the adoptive parents and birth parents are able to co-operate well – can provide the child with the type of nurturing and stability that might otherwise be provided within a family placement”.

“Adoption-from-care has given many children and young persons the much greater security of a permanent home,” he adds, “compared to the earlier situation where more children and young people remained under the parental responsibility of the Minister and were often subject to multiple placement changes.”

Read the full article here.